World

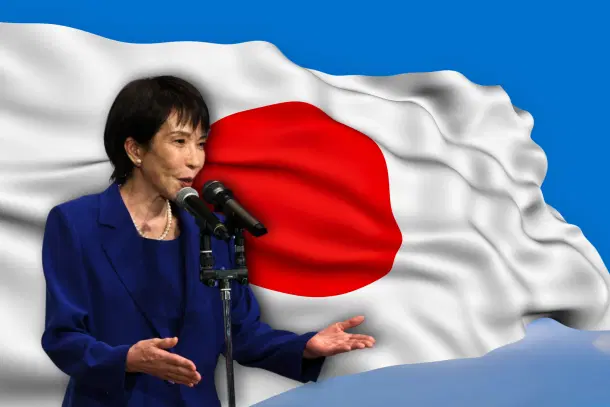

End Of Japan's Pacifist Era? New PM Takaichi's Rise Signals A Harder Line On China

Prakhar Gupta

Oct 11, 2025, 08:00 AM | Updated Oct 10, 2025, 02:26 PM IST

Save & read from anywhere!

Bookmark stories for easy access on any device or the Swarajya app.

With only days left in office, Japanese Prime Minister Shigeru Ishiba is preparing to deliver a speech marking the 80th anniversary of Japan’s World War II surrender, a politically charged subject that has long divided his party. It would be a parting move that could unsettle the agenda of his incoming, more hardline successor.

Despite pressure from within the Liberal Democratic Party to avoid contentious references, Ishiba is expected to invoke Japan’s wartime past and call for the restoration of a censored 1940 anti-war speech that condemned the invasion of China. Conservatives worry that reopening debates over historical responsibility at a moment of political transition could complicate the incoming government’s agenda.

His successor, Sanae Takaichi, a staunch conservative and soon to be Japan’s first female prime minister, is preparing to take office next week. Her rise marks a decisive shift in both domestic politics and Japan’s approach to security and foreign policy.

Japan’s postwar constitution is famously pacifist. Article 9, drafted during the U.S. occupation after World War II, renounces war as a sovereign right and prohibits Japan from maintaining land, sea, and air forces. It was intended to prevent the country from returning to the militarism that had engulfed Asia, shaping Japan’s global identity for decades.

For decades, pacifism was not only legal but political. Defence budgets remained low, military operations were limited to self-defence, and public opinion strongly favoured restraint. Japan’s postwar identity was built around economic reconstruction rather than military strength, and foreign policy was carefully calibrated to avoid provoking neighbours.

Even so, pacifism has never been absolute in practice. In 1954, Japan established the Self-Defence Forces at the minimum necessary for national defence. Subsequent governments gradually expanded their capabilities. The landmark 2014 security legislation under Shinzo Abe allowed Japan to engage in limited collective self-defence. Japan could now defend allies under attack, a legal reinterpretation that bypassed the need for constitutional amendment but represented a notable step away from strict pacifism.

Despite these incremental shifts, Article 9 remains unchanged on paper. Any formal revision would require supermajorities in both houses of the Diet and a public referendum, a political hurdle that has kept legal pacifism intact. Yet the gap between constitutional pacifism and practical militarisation has been narrowing for years, and Takaichi’s leadership threatens to accelerate that process.

Takaichi has made her hawkish vision clear. A protégé of Abe, she supports explicitly recognising the Self-Defence Forces in the constitution and emphasises Japan’s right to collective self-defence. She has promised to raise defence spending beyond 2 per cent of GDP and accelerate implementation of the national defence strategy. For Takaichi, Japan’s military is not a reactive instrument but a tool of strategic autonomy.

Her agenda also prioritises interoperability with U.S. forces. This includes joint contingency planning for Taiwan and hosting U.S. intermediate-range missiles on Japanese soil. Such steps deepen security integration with Washington, but they are inherently provocative to Beijing. Takaichi’s rhetoric repeatedly identifies China as a strategic threat, criticising its military expansion and economic coercion.

Where previous leaders sometimes masked expansion under legal reinterpretation, Takaichi seeks clarity and visibility. She frames Japan’s Self-Defence Forces as central to national security and deterrence. This is a more assertive posture than anything seen under past administrations, signalling that Japan’s pacifist identity is being subordinated to a more confrontational reality.

The erosion of pacifism is not limited to defence. Takaichi’s economic agenda complements her security strategy. She embraces a revival of Abenomics alongside a focus on economic security and supply-chain resilience. While committed to trade liberalisation with partners such as the CPTPP and the European Union, she emphasises reducing dependence on China.

As Japan’s former Minister of Economic Security, Takaichi has pushed policies designed to diversify supply chains for critical industries including semiconductors, rare earths, and other strategic materials. Her team promotes investment in AI, biotechnology, energy, and defence-related technology, blending growth ambitions with security imperatives.

This economic recalibration reinforces her defence objectives. Reducing reliance on China strengthens Japan’s strategic autonomy and insulates it from Beijing’s economic coercion. Yet it also shifts the bilateral relationship toward rivalry. Japanese companies have long depended on Chinese markets and manufacturing. Deliberate decoupling, even partial, carries economic costs and sends a clear strategic message.

Takaichi’s ideology is often described as Abe-ism, the conservative-nationalist blueprint championed by Shinzo Abe in his later years. She has publicly aligned herself with Abe’s vision of a strong Japan capable of projecting power and defending its interests. Symbolically, she has visited the Yasukuni Shrine, which honours Japan’s war dead, including Class-A war criminals, a gesture that China interprets as provocative.

On Taiwan, Takaichi is explicit. She has cultivated close ties with Taiwan’s leadership and supports its inclusion in international trade and security frameworks. She has stated that Japan would come to Taiwan’s defence in a crisis. For Beijing, these moves are viewed as direct interference in what it considers its sovereign affairs.

Under Takaichi, multiple tensions with China are likely to intensify. Security exercises, public support for Taiwan, and moves to formally embed the Self-Defence Forces in the constitution signal an increasingly assertive Japan. Economic decoupling will further reduce the stabilising effects of trade and investment, transforming what has long been a complex but manageable bilateral relationship into one characterised by strategic competition.

Symbolism will remain consequential. Visits to Yasukuni, revisions of textbooks, and public statements on historical grievances will provoke Chinese ire. Even routine defence exercises in the Taiwan Strait or Japan’s support for Taiwan’s participation in international forums will be interpreted by Beijing as crossing red lines. Chinese state media have already taken an alarmist tone, signalling low trust from the outset.

Some constraints remain. Takaichi’s coalition partner, the pacifist Komeito party, could temper certain moves. Japan will likely maintain selective economic engagement with China, balancing security priorities against commercial interests. But the overall trajectory is unmistakable. Security and economic policies under Takaichi are designed to reduce vulnerability to China and assert Japan’s autonomy.

The long-term implications are profound. Japan’s postwar pacifist identity, which once strictly limited military capability, has been eroding for decades. What began as careful reinterpretations of Article 9 under successive governments has now evolved into an assertive agenda that openly questions the limits imposed by the constitution. Takaichi could be the leader who finally pushes Japan past the constraints of pacifism in both legal and practical terms.

Her approach is both ideological and pragmatic. Abe-ism provides the political template, emphasising national pride, historical revisionism, and a muscular security posture. At the same time, practical threats—China’s military expansion, North Korean missiles, and economic coercion—justify a departure from pacifism as a matter of national survival. Japan is no longer willing to rely solely on alliance guarantees; it seeks autonomous capability backed by economic and military measures.

This convergence of ideology, strategy, and policy is reshaping Japan’s relationship with China. Defence posture, economic decoupling, and nationalist signalling collectively indicate that Japan views China as a rival rather than a partner. For Beijing, Takaichi’s Japan will be harder to predict, less deferential, and less willing to tolerate unilateral Chinese action in the region.

Already, tensions are likely to manifest in multiple arenas. Taiwan is the most immediate flashpoint, but territorial disputes in the East China Sea, technological competition, and trade frictions will compound the strain. Japan’s willingness to formalise the Self-Defence Forces’ constitutional status, host U.S. missiles, and defend Taiwan are all steps that challenge the assumptions of a postwar regional order.

Even if Japan maintains diplomatic engagement where necessary, the underlying strategic logic is clear. Takaichi’s Japan prioritises deterrence, autonomy, and resilience over conciliation. Pacifism, once a defining national characteristic, is being subordinated to a hard-nosed assessment of security imperatives.

For observers in Beijing, the message is unmistakable. Japan is preparing for a world in which the postwar constraints of Article 9 are no longer an effective limit on national power. Security cooperation with the U.S., economic decoupling from China, and nationalist symbolism all reinforce the idea that Japan is entering a new phase. The period of cautious restraint that has characterised Japan since 1945 is giving way to a more assertive era.

Takaichi’s tenure will test the balance Japan has maintained for decades. The country’s postwar identity, its economic model, and its security strategy are all being recalibrated. A generation ago, her agenda would have been unthinkable. Today, it reflects both the pressures of the region and a deliberate effort to redefine Japan’s role in East Asia.

The key takeaway is that pacifism in Japan is no longer a fixed point. Through incremental reinterpretation and now a more explicit political agenda, Japan is asserting the principle that its military and economic policies must reflect real-world imperatives.

The changes under Takaichi will test the uneasy balance Japan has struck since World War II. A generation ago, her agenda would have been unthinkable. Today, it is a response to new threats and also a reminder that Japan’s pacifist era has been steadily winding down. Takaichi’s premiership may well mark the point at which pacifism is no longer a guiding principle but a historical artefact.

Prakhar Gupta is a senior editor at Swarajya. He tweets @prakharkgupta.